Estimated reading time: 3 minutes

Burning down the streets¶

The whole thing makes me wonder whether a modern reintroduction of the skimmington ride for social media is long overdue.

—Stephen Roberts, eloquent friend

A few months ago a work colleague asked if I could help his wife with an art project she was working on. The premise was simple and rather enticing, so I jumped at the chance.

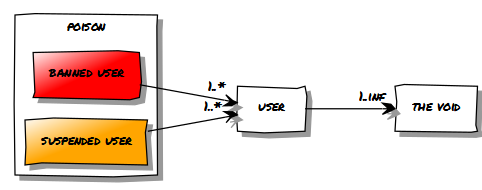

The basic idea was to mine Twitter for its copious poison and visualise any patterns that emerge. We quickly hit upon the idea that some poison was so obvious that even the Twitter folks would acknowledge and reject it, and piggybacking off of that would trim down the work considerably.

Mining the abyss¶

My task was simple: ingest a massive lump of JSON, process it somehow and spit out results that could be used in an artsy manner that I would likely not understand.

The initial concept worked by scanning a firehose of tweets for keywords which seemed likely to be hugely poisonous, and then create a DAG as the basis to rate users who were retweeting them. Later versions were self-training using a naïve Bayes classifier, which allowed us to find offensive tweets using words I was previously happily unaware of.

Early on it became obvious that another effect presented itself. There were masses of users who were retweeting users who would later be banned, and those retweeting users would move on to retweeting new users who themselves would often end up banned.

The interesting point to me was that there were large numbers of actual users — not bots — who redirect the hate storm and almost nothing else. Many of these users were in an anechoic chamber, sucking in tweets from many users and spitting them back out to virtually no one. I thought it would be interesting to work only on the final nodes; weighted by those users who receive close to no retweets and low user interaction but with histories of retweeting large numbers of banned and suspended users. I called it RageRank, because I’m aware of Page Rank and lack an imagination.

The arty part of the project became known informally as Final Spite, after an early visualisation effort with animated clone after clone walking along a Final Fight background spewing a tweet bubble as their energy bar depleted. Each new visualisation started from a map, much like the game’s levels, and showed a real city with its real occupants. The intent was to allow people to experience a location they knew but with its foetid underbelly exposed.

What happened next?¶

What happened next saddened and surprised me in equal quantities; visitors to the site doxxed a heap of the displayed retweeters almost immediately. So much in fact that the site was taken down within a day, and the work became a mostly offline exhibit in a little gallery for other evening school art students.

I can understand the sentiment in many ways, and perhaps should have seen it coming. When I saw a person I knew in a visualisation I was ashamed, truly ashamed. I mean not to the point of thinking it is appropriate to post all their personal details for the internet vigilantes, but enough that I knew I would not want to be linked to them through work or social circles.

However, the end result was really neat even on the smaller canvas it has to live on. Seeing that level of vitriolic rage is not fun, but realising that much of it is vented in to nowhere does soften it a little.

Fall out¶

One of the things that surprised me most was that initially I had primed the data by looking at users who followed users that have been suspended or banned. After digging in to a few examples to verify the method’s efficacy I noticed that there are bidirectional follows to the final nodes where one user appears to be the polar opposite of the other, almost in an Alf Garnett versus Peppa Pig scale.

It took me a while to think of a possible cause — beyond a simple modelling error — that could explain this. Sadly after recognising a top five rage retweeter in a local town it became somewhat obvious, there are occasionally business and familial ties involved. There are seemingly swathes of the populace who choose to accept public association with the caustic members of society, even when there is a simple unfollow button you can hit to distance yourself from them.

Let us be frank and honest for a moment. You’re giving the appearance of tacit approval to people’s views when you continue to follow them, even if you’re not actively engaging with them. The simple act of not confronting them is normalising the behaviour. If you’re not calling them out on it, you’re doing yourself and society at large a serious injustice.

Authenticate this page by pasting this signature into Keybase.

Have a suggestion or see a typo? Edit this page